Art History: A Beginner’s Guide to Major Movements

Introduction

Art history is not just a timeline of paintings and sculptures—it’s the story of humanity told through color, form, and expression. From cave drawings to digital installations, each artistic movement reflects the cultural, political, and emotional tides of its era. For those just stepping into the world of visual art, understanding the major movements of art history can provide not only context but also a deeper appreciation for the artworks we encounter today.

In this beginner’s guide, we’ll explore the most influential movements that shaped the course of art history. Each era introduced new styles, ideas, and innovations that helped build the rich tapestry of global art. Whether you’re an aspiring collector, student, or simply a curious observer, this overview will serve as your entry point into the compelling world of artistic evolution.

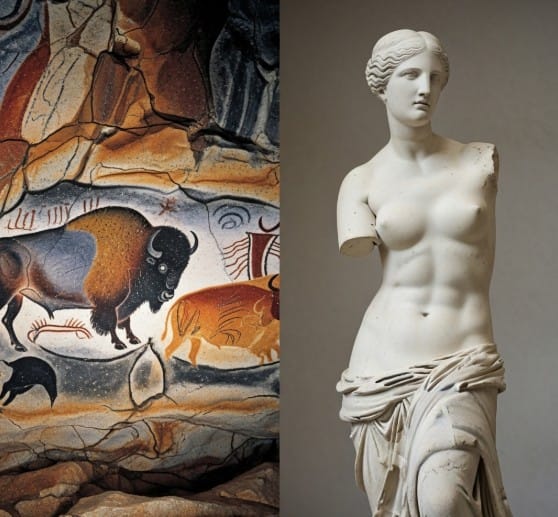

Prehistoric and Ancient Art

Art began before history was written. Prehistoric art, such as cave paintings in Lascaux, France or the Venus of Willendorf figurine, was deeply symbolic and often spiritual in nature. These works offered early humans a way to make sense of their world—through ritual, storytelling, and identity.

As civilizations developed, so did artistic sophistication. Ancient Egyptian art emphasized order, permanence, and divinity, seen in hieroglyphs and grand tomb frescoes. Meanwhile, Greek and Roman art embraced proportion, beauty, and human anatomy, producing sculptures and architectural marvels that influenced centuries of art to come.

Medieval Art

Spanning from roughly the 5th to the 15th century, medieval art was deeply intertwined with religion. In Europe, Christian themes dominated, expressed through illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, and Gothic cathedrals.

Unlike classical art, which focused on realism and beauty, medieval art prioritized symbolism and devotion. Iconography played a major role in conveying spiritual narratives to largely illiterate populations.

Meanwhile, in the Islamic world, intricate geometric patterns, arabesques, and calligraphy flourished in mosques and manuscripts—forms of visual poetry rooted in religious expression.

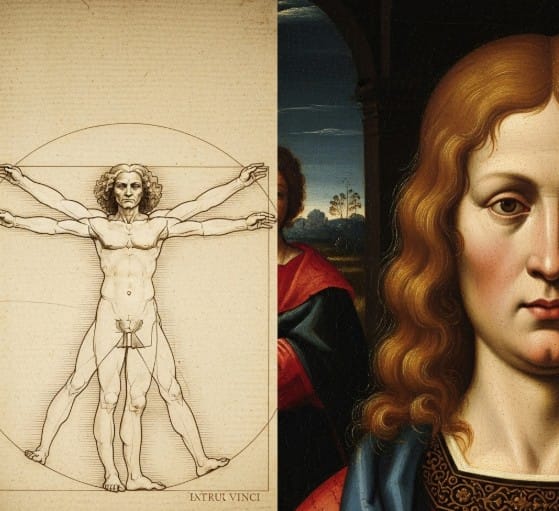

Renaissance (14th–17th Century)

The Renaissance marked a rebirth of classical ideals, driven by humanism and a new interest in the natural world. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael revolutionized painting and sculpture by applying perspective, anatomy, and emotion.

Art became more realistic, dynamic, and intellectually engaging. The period also saw the rise of individual artistic genius, with patrons like the Medici family funding elaborate commissions that blended art, science, and philosophy.

The Northern Renaissance, led by artists such as Jan van Eyck and Albrecht Dürer, brought hyper-realistic detail and symbolism into focus.

Baroque (17th Century)

If the Renaissance was about balance and harmony, the Baroque was about drama, grandeur, and emotion. Baroque artists like Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt used intense contrast (chiaroscuro), movement, and theatrical compositions to captivate the viewer.

Baroque art was often commissioned by the Church or monarchies to evoke awe and reinforce authority. It was art as spectacle—opulent, dynamic, and filled with life.

In Spain, artists like Diego Velázquez produced court portraits that blended realism with psychological depth, while in France, Baroque merged into the decorative and elegant Rococo style.

Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Late 18th–Early 19th Century)

As Enlightenment ideals took hold, Neoclassicism emerged as a return to order, reason, and classical restraint. Inspired by ancient Greece and Rome, artists like Jacques-Louis David emphasized stoicism, civic virtue, and heroic themes.

Romanticism, in contrast, was emotional, imaginative, and rebellious. Romantic artists such as Eugène Delacroix and Francisco Goya responded to industrialization and political unrest with passionate, often dark imagery. Nature, revolution, and the sublime were central themes.

These movements ran parallel—reflecting two sides of humanity’s quest for meaning: one rational, the other emotional.

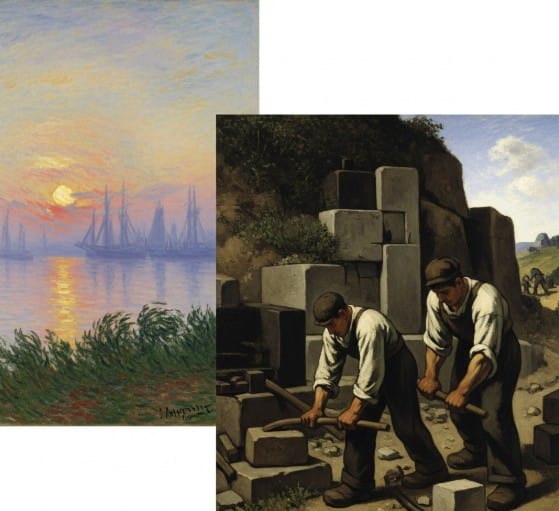

Realism and Impressionism (Mid–Late 19th Century)

Realism was a reaction against Romanticism’s dramatization. Realist artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet focused on everyday life, depicting peasants, laborers, and urban scenes without idealization.

Then came the Impressionists, who challenged academic art with loose brushwork and an obsession with light and color. Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted modern life with spontaneity and vibrancy, often working en plein air to capture natural light.

Though initially criticized, Impressionism paved the way for modern art, introducing a freer, more personal visual language.

Post-Impressionism and Symbolism (Late 19th Century)

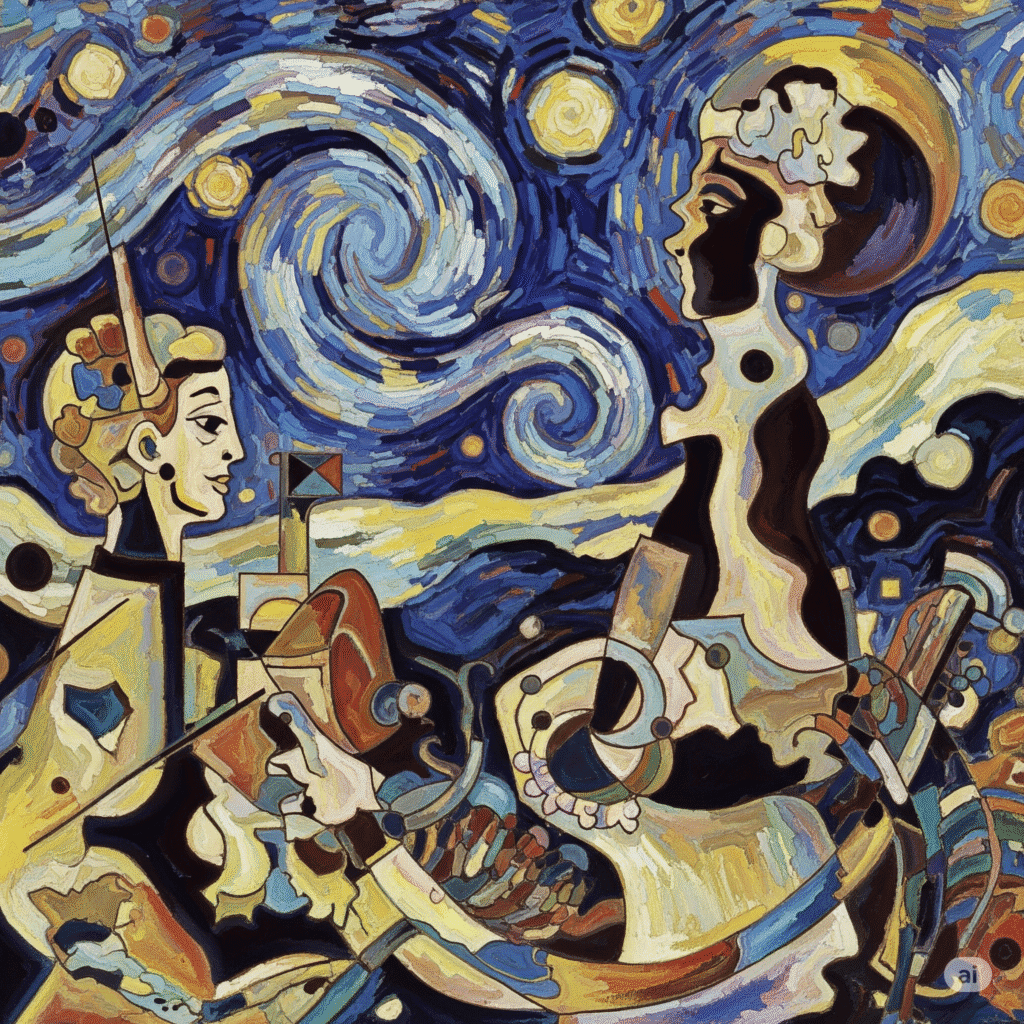

Artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Paul Gauguin pushed Impressionism further by exploring form, emotion, and symbolism. Their bold colors and innovative techniques influenced nearly every modern movement that followed.

Symbolist painters such as Gustav Klimt and Odilon Redon turned inward, creating dreamlike works full of allegory, myth, and introspection. These artists laid the groundwork for abstraction and expressionism.

Modern Art Movements (20th Century)

The 20th century was an explosion of experimentation. Traditional boundaries were broken, and countless new movements emerged.

Fauvism: Led by Henri Matisse, Fauvism embraced wild color and emotional expression.

Cubism: Developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism deconstructed form and perspective, laying the foundation for abstraction.

Expressionism: German artists like Edvard Munch and Wassily Kandinsky expressed psychological angst and inner turmoil.

Dada and Surrealism: Born from the trauma of World War I, these movements used absurdity, dreams, and subconscious imagery to challenge societal norms. Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and Man Ray were among its key figures.

Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism (Mid 20th Century)

Post-WWII America became the center of the art world. Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko created large-scale works emphasizing spontaneity, emotion, and the subconscious.

In contrast, Minimalism, led by Donald Judd and Agnes Martin, focused on simplicity, repetition, and industrial materials. It was about clarity and reduction—less was more.

Pop Art and Conceptual Art (1960s–70s)

Pop Art, with artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, used imagery from advertising and consumer culture to blur the lines between high and low art. It was colorful, ironic, and instantly recognizable.

Conceptual Art questioned the very definition of art. Artists like Joseph Kosuth and Yoko Ono prioritized ideas over aesthetics, asking: Is the thought behind the work more important than the object itself?

These movements shifted the focus from beauty to meaning, from object to concept.

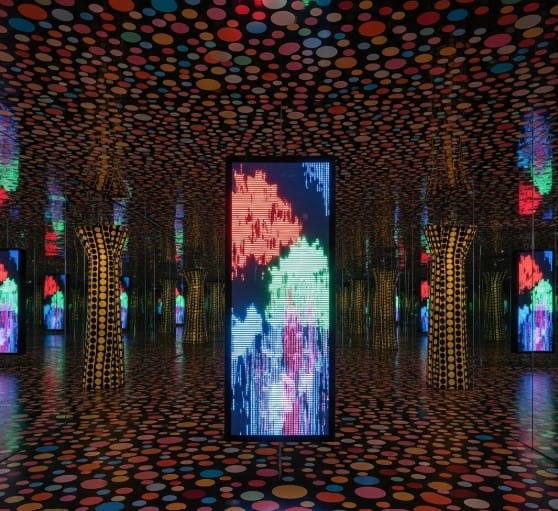

Contemporary and Digital Art (1980s–Today)

Contemporary art defies neat categories. It includes installation, performance, video, and socially engaged practices. It’s global, diverse, and often political.

Artists like Ai Weiwei, Kara Walker, and Yayoi Kusama address issues of identity, race, environment, and power. Meanwhile, digital art has introduced new forms like NFTs, virtual installations, and AI-generated works.

In this era, the viewer often plays a participatory role, and art becomes a conversation, not just an object.

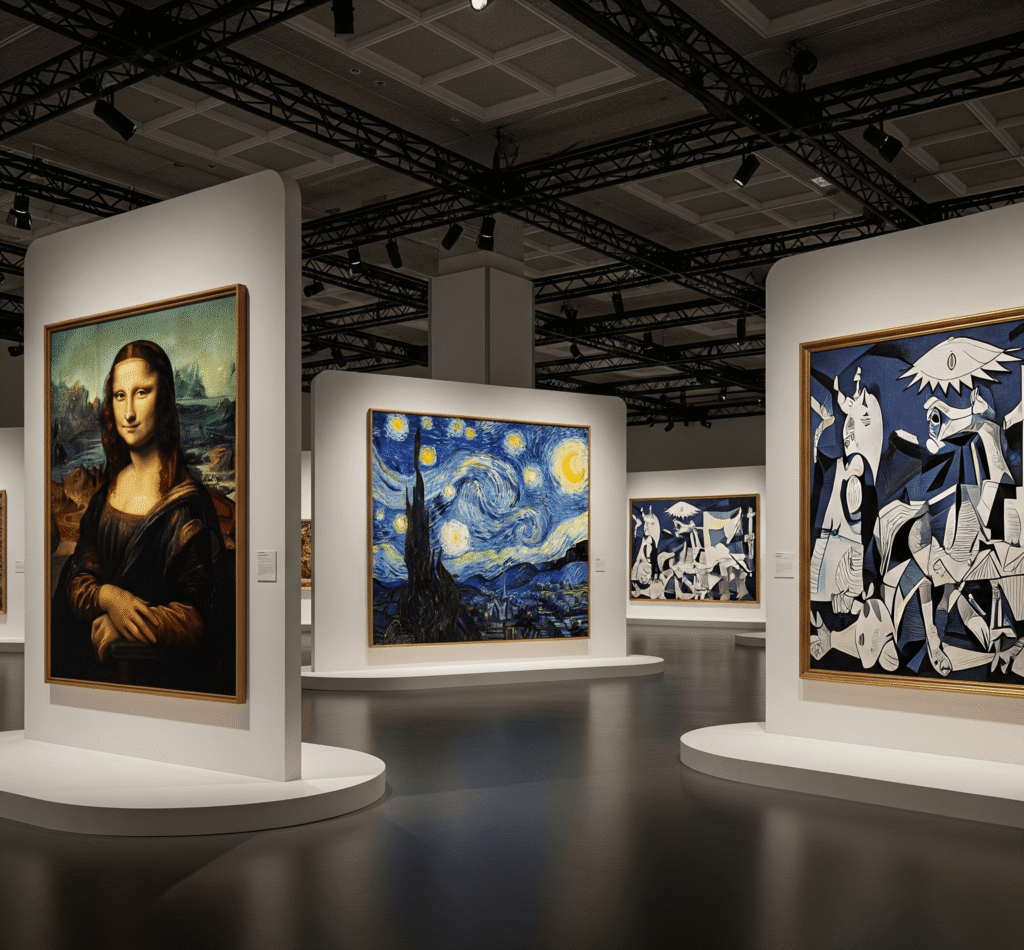

Why Art History Matters

Understanding art history isn’t just about memorizing dates or artists. It’s about recognizing how culture evolves, how people express their fears and dreams, and how creativity shapes society.

Each movement builds upon or reacts to what came before. Learning this context enriches our experience of art and deepens our appreciation. When we understand why a painting looks the way it does, or what social issues it’s responding to, it comes alive.

Art history also helps us recognize patterns—how creativity flourishes during times of upheaval, how innovation often begins at the margins, and how beauty can be both protest and poetry.

How ISKUSS Connects Past and Present

At ISKUSS, we celebrate the evolution of art through curated collections that honor both tradition and innovation. Our catalog includes contemporary works influenced by major historical movements, reflecting the continuity of artistic expression.

Whether you’re a lover of Renaissance elegance or drawn to abstract minimalism, ISKUSS offers something that connects you to the larger story of art. Our artists are rooted in culture yet embrace modern forms, creating a bridge between the old and the new.

Explore timeless and contemporary works at ISKUSS and find pieces inspired by the great movements of art history.

Learn more about art movements from The Art Story

Conclusion: Your Journey Through Art History Begins Now

Art history is not something to be mastered overnight. It is a journey—a lens through which we see not just art, but ourselves. By understanding the major movements and their significance, we gain tools to navigate the visual world with more depth and curiosity.

Start small. Pick a movement that resonates with you. Visit a museum. Read about an artist. Look closely. Reflect deeply. Over time, you’ll discover that art history is not just history—it’s a living, breathing part of our shared humanity.