Art and Empire: How Colonialism Influenced Artistic Expression

Introduction

The entanglement of art and empire is one of the most defining and complex relationships in global art history. From the bustling ateliers of Mughal India to the salons of Paris and the tribal workshops of Africa, colonialism drastically altered how art was produced, perceived, and preserved. This blog explores how colonialism and art intersected to reshape artistic expression across continents—highlighting both cultural disruption and creative resistance.

1. Why Study Colonial Influence on Art?

Colonialism wasn’t just about land and labor—it was also about cultural control. Art became a tool of domination and diplomacy, a mirror of imperial ideology. At the same time, artists in colonized societies used creative expression to preserve identity, critique power, and sometimes to survive.

Understanding the link between colonialism and art helps us unpack larger themes of cultural memory, resistance, appropriation, and global aesthetics.

2. The Aesthetic Ideology of Empire

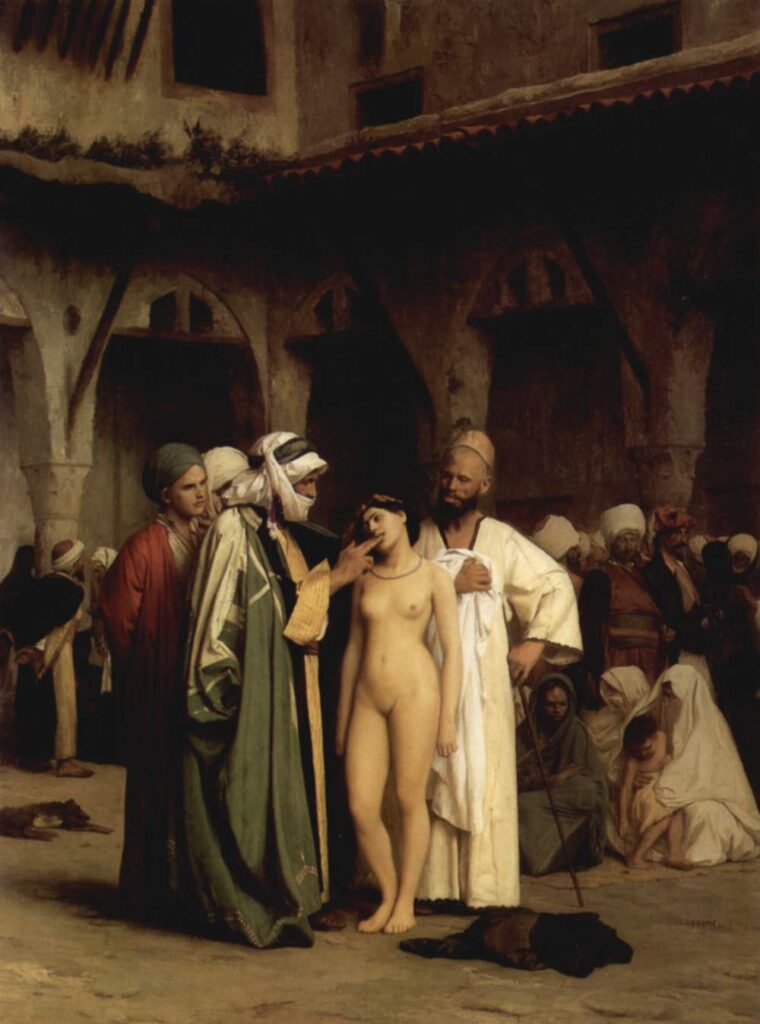

Empires used visual art as propaganda to legitimize their rule. This included:

- Paintings glorifying colonial conquests

- Architectural projects in classical European styles

- Portraiture of colonial administrators and ‘exotic’ subjects

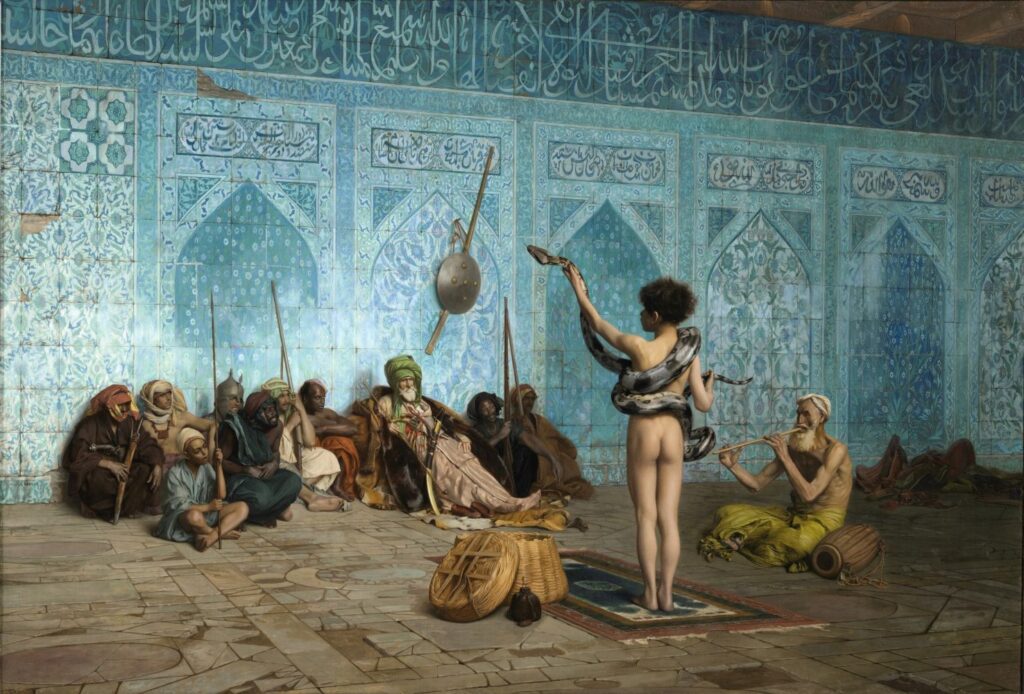

In British India, for instance, the East India Company commissioned works to depict their civilizing mission. Similarly, French Orientalist paintings often romanticized the Middle East and North Africa, masking the violence of occupation with sensual imagery.

Art wasn’t neutral—it was embedded in the ideological machinery of empire.

3. Appropriation and Erasure: The Colonial Gaze

The colonial gaze refers to how colonizers viewed and represented the “other”—the colonized. This gaze often reduced complex cultures into stereotypes, stripping artworks of their spiritual, functional, or social context.

Key Features:

- Artifacts looted and displayed as trophies

- Indigenous styles labeled as “folk” or “primitive”

- Erasure of native artistic lineages in favor of European methods

The 1897 British looting of the Benin Bronzes is a stark example. These intricate sculptures, which once served ritual and historical purposes, were taken and exhibited in European museums as “curiosities.”

4. Artistic Production in the Colonized World

Colonial regimes often transformed local artistic ecosystems:

- Patronage shifted from indigenous rulers to colonial officials.

- Art schools imposed European techniques and suppressed traditional forms.

- Market demand influenced artisans to create for export rather than community use.

For example, the British established art institutions like the Government School of Art in Calcutta (1854), promoting realism over indigenous aesthetics.

Yet, even under these constraints, artists found ways to adapt and innovate, blending imposed styles with ancestral traditions.

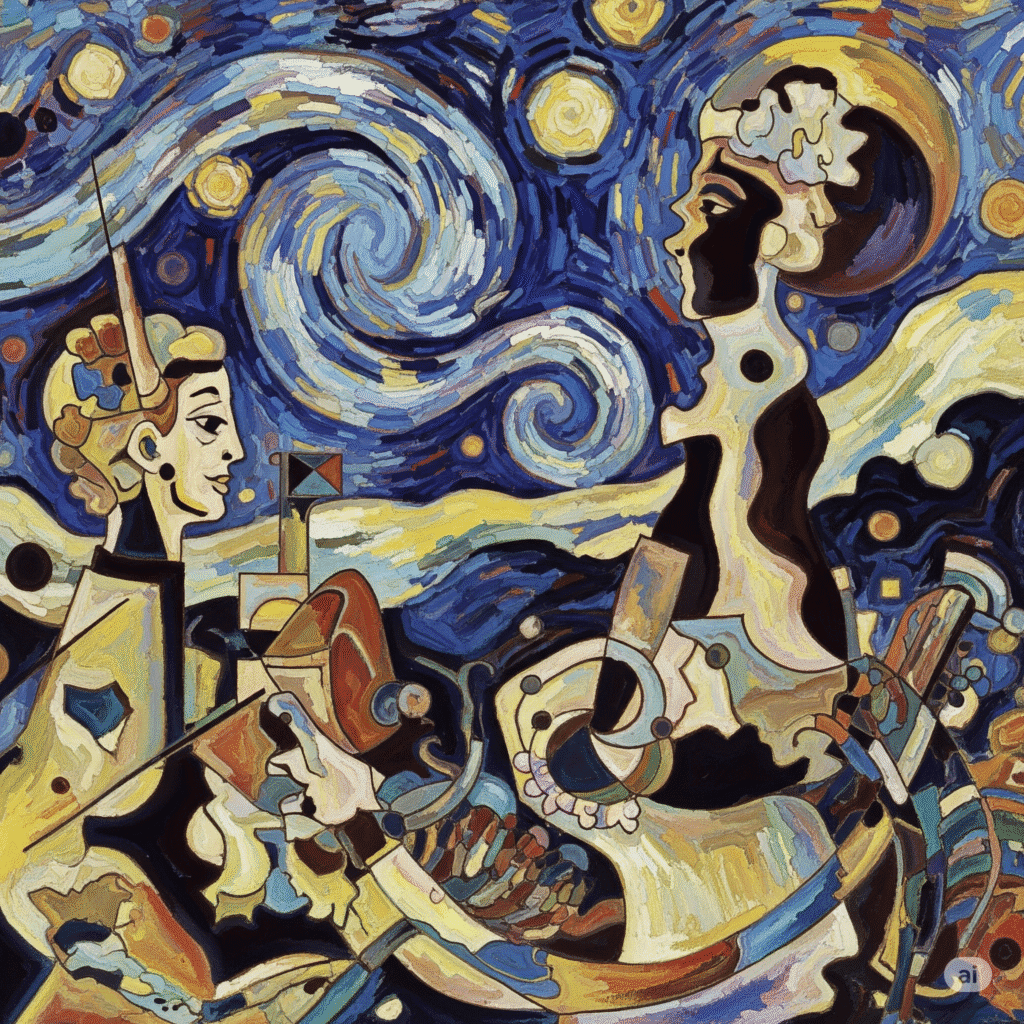

5. Hybridity: When Worlds Collide

The colonial encounter produced hybrid art forms—works that merged indigenous techniques with European styles or vice versa. This hybridity was not always forced; sometimes it represented a strategic negotiation of identity.

Examples:

- Company Paintings in India: Local artists depicted scenes in European watercolor style.

- Creole art in the Caribbean: Merged African, European, and Indigenous motifs.

- African textiles incorporating colonial symbols to tell subversive stories.

Hybridity became a space of both conflict and creativity—a way to navigate fractured identities.

6. Resistance Through Art

Art also served as silent defiance. Artists and artisans used their work to resist cultural imperialism and assert autonomy.

- Mahatma Gandhi’s call for khadi (handspun cloth) was not just economic—it was an aesthetic act of resistance.

- In Algeria, anti-colonial graffiti became a tool of protest.

- African masks and sculptures, once derided as pagan relics, became powerful symbols of cultural pride in the 20th century.

Subaltern artists reclaimed their narratives using visual forms as a language of sovereignty, survival, and subversion.

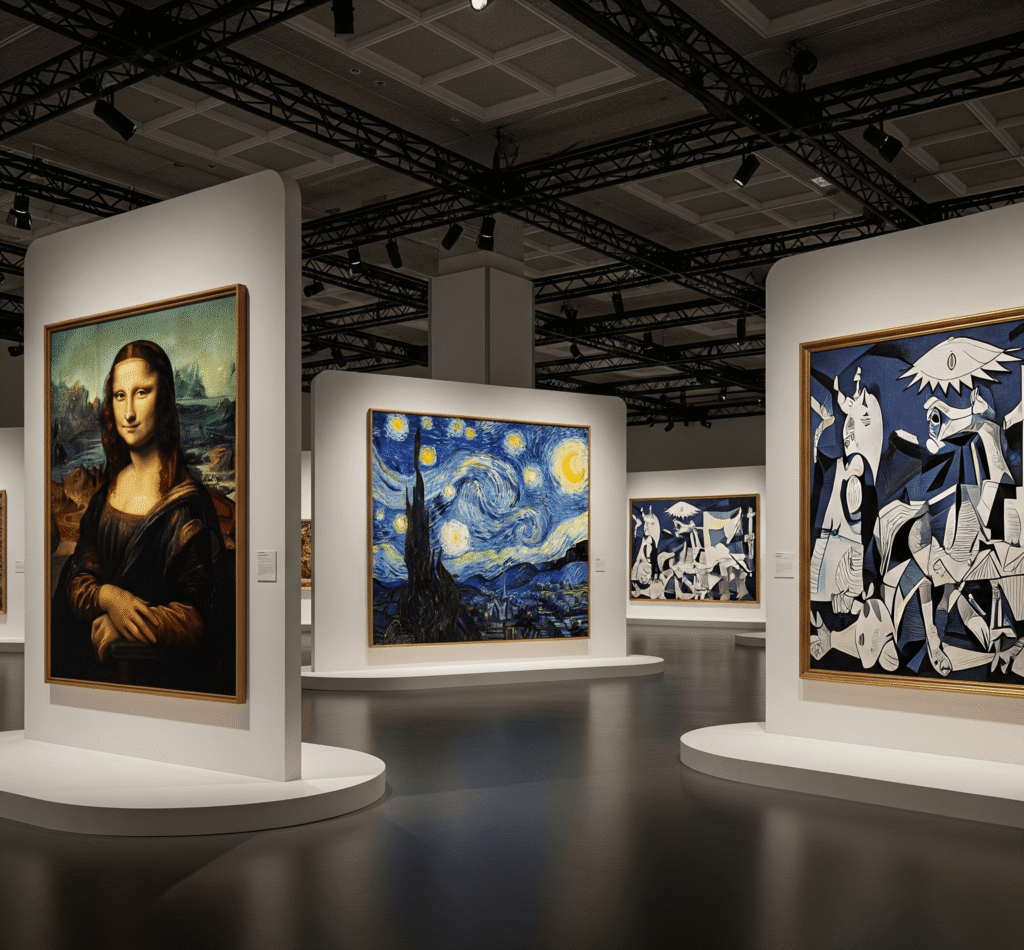

7. Museums and the Politics of Display

The colonial legacy is deeply embedded in how art is curated today.

- Museums in Europe house thousands of looted artifacts.

- Displays often strip objects of context, presenting them as timeless and authorless.

- Debates around restitution and decolonizing museums are gaining momentum.

A 2021 report commissioned by the French government recommended the return of African artifacts to their countries of origin—a historic step toward rectifying colonial plunder. Read more on restitution here.

8. Postcolonial Reflections in Contemporary Art

Contemporary artists around the world continue to grapple with the legacy of empire.

Key Themes:

- Memory and trauma

- Cultural fragmentation

- Reappropriation of colonial imagery

Artists like Kara Walker, Yinka Shonibare, and Atul Dodiya use colonial motifs to question history, identity, and power. Their work dismantles the old narratives and offers new visual languages rooted in postcolonial experience.

ISKUSS, too, offers curated prints and works that revisit traditional art forms shaped by colonial contact. Explore how artists reinterpret cultural legacy at ISKUSS.

9. Case Studies: India, Africa, and the Caribbean

India

Under British rule, Indian art was categorized and institutionalized:

- Miniature painting schools dwindled.

- Traditional mural forms (like Kerala temple murals) were undervalued.

- The Bengal School of Art, led by Abanindranath Tagore, reacted against colonial realism with spiritual symbolism rooted in Indian tradition.

Africa

Art was often dismissed as “craft” by colonizers. Yet:

- Traditional African sculptures influenced European modernists like Picasso.

- Contemporary African artists now reclaim indigenous forms in global exhibitions.

- Adinkra symbols, once suppressed, are now celebrated in textile and digital art.

Caribbean

Colonial legacies of slavery, plantation economy, and migration shaped Caribbean art.

- Artists mix African heritage, indigenous influences, and European colonial references.

- Calypso, carnival art, and muralism are vibrant postcolonial expressions.

10. Final Thoughts

The impact of empire on art was profound—but not absolute. While colonialism altered artistic landscapes, it also provoked creative resistance, cultural fusion, and critical reflection. The postcolonial world continues to reckon with this legacy, challenging us to rethink how we view, value, and validate art across cultures.

In exploring colonialism and art, we uncover not only a history of domination, but also one of resilience, hybridity, and the enduring power of visual expression.

11. References and Further Reading

- Said, Edward. Orientalism

- Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth

- Restitution of African Art – The Guardian

- ISKUSS – Explore Postcolonial Artistic Reflections